-

Fugitive Slave Laws

-

Equal Protection

-

Affirmative Action

-

Ballot Measures

-

Religious Freedom

-

Education Equity

Fugitive Slave Laws: Bids for Freedom

8th Grade U.S. History

Overview & Background:

When California joined the United States as a free state as part of the Compromise of 1850, it entered the nation-wide debate on slavery that sharply divided the North and South. Part of that compromise was the enactment of a national Fugitive Slave Act which compelled citizens to help return fugitive slaves to their owners, denied fugitives a right to a jury trial, and put a fugitive’s case in the hands of a federal commission.

Despite the state constitution outlawing slavery, slave-holding persisted within California’s borders, and the state legislature passed its own Fugitive Slave Law in 1852 (Wherever There’s a Fight, p.123-124). Slaveholding migrants to the “Golden State” attempted various ways of holding onto the African Americans they considered to be their property.

In California’s early years, two African American freedom seekers, Bridget “Biddy” Mason and Archy Lee sought their freedom through the state judicial system. In contrast to Dred Scott in Missouri, a slave state, they gained their freedom. By comparing and contrasting these three court cases, students will understand how the judicial system could be a route to freedom, albeit risky, treacherous, and not always successful. Students will evaluate the judicial system as a route to freedom based on factors such as location, African American community organizations and networks, and judges’interpretations. Lastly, students will gain a California perspective on African Americans seeking their freedom through the courts. This lesson is best implemented in a unit on African American History prior to the Civil War or causes of the Civil War.

Focus Question & Teaching Thesis:

Focus Question:

How successful were African Americans who used the U.S. judicial system as a way to gain freedom prior to the Civil War?

Teaching Thesis:

Since the United States was divided in the debate over slavery, the judicial system was also fractured between the North and South in the decade before the Civil War. The road to freedom through the judicial system was risky, treacherous, and not always guaranteed to African Americans seeking freedom, even if their cases were sound; consequently, freedom gained through the courts was dependent on a number of factors, including place, judges’interpretations, and African American community networks.

History-Social Studies Standards:

Four content standards are addressed in this multi-day lesson. By learning about the stories of Bridget Mason, Dred Scott, and Archy Lee, students understand attempts by African Americans to realize the ideals set forth in the Declaration of Independence and how those attempts connected to the compromises regarding slavery.

8.9 – Students analyze the early and steady attempts to abolish slavery and to realize the ideals of the Declaration of Independence.

8.9.4 – Discuss the importance of the slavery issue as raised by the annexation of Texas and California’s admission to the union as a free state under the Compromise of 1850.

8.9.5 – Analyze the significance of the States’Rights Doctrine, the Missouri Compromise (1820), the Wilmot Proviso (1846), the Compromise of 1850, Henry Clay’s role in the Missouri Compromise and the Compromise of 1850, the Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854), the Dred Scott v. Sandford decision (1857), and the Lincoln-Douglas debates (1858).

8.11.2 – Identify the push-pull factors in the movement of former slaves to the cities in the North and to the West and their differing experiences in those regions (e.g., the experiences of Buffalo Soldiers).

Learning Objectives:

- Students will understand the court cases of Bridget Mason, Dred Scott, and Archy Lee in the context of African Americans realizing the ideals of the Declaration of Independence.

- Students will compare and contrast these three court cases on at least three factors.

- Students will evaluate the success or failure of African Americans seeking freedom through the courts based on their analysis of the cases.

Duration:

Three to five 45-minute class periods

Materials:

- Excerpt from Wherever There’s a Fight, Ch. 4, p.123-128 (one copy for each student)

- Textbook excerpt on the Dred Scott v. Sandford case (textbook choice dependent on school and district; one copy for each student)

- Reading Organizer Handout (one for each student)

Prior Knowledge/Context:

- Understanding of the main ideas and effects of compromises regarding slavery on the nation and its people in the first half of the 1800s including the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and the Compromise of 1850

- Understanding of the concepts of three branches of government, checks and balances, and federalism

- Knowledge of the different ways in which African Americans fought for freedom prior to the Civil War, including use of petitions, freedom of speech, etc.

- Basic knowledge of a writ of habeas corpus

- Basic knowledge of how a case is brought to court

Sequence of Activities:

- Introduce the lesson by posing the question, “Why do people go to court?” Answers should elicit both the motivations and aims of plaintiffs. Answers can also reveal to teachers the level of pre-teaching around law-specific vocabulary that will be necessary for students.

- Transition into the lesson by telling students that going to court was one way that African Americans fought for freedom from slavery in the early 1800s. Put this statement into historical context by having students brainstorm additional ways that African Americans fought for their freedom from slavery prior to the Civil War, such as organizing the Underground Railroad and writing autobiographies. Briefly discuss the success of the additional examples along with some of the factors that influenced them.

- Review key vocabulary as necessary.

- Pass out the Reading Organizer . Model how you would like students to read and analyze Bridget Mason’s case using the excerpt from Wherever There’s a Fight, p. 123-125 on Bridget Mason and the Reading Organizer . Using your adopted textbook, complete the Reading Organizer for Dred Scott. For the third case, read the excerpt from Wherever There’s a Fight, p.125-128 on Archy Lee and complete the Reading Organizer . Refer to the Teacher Key as needed.

- As a class, discuss which of the cases was successful and the reasons for success.

- Review the completed Reading Organizer by asking students to look for similarities and differences among the three cases. Record the similarities and differences in a T-chart on the board as a class. Refer to the Teacher Key as needed. Then ask students to consider which similarities or differences seem to be most important in determining the success or failure of the court cases. Using the last column of the Reading Organizer , guide students to the three most important factors: location in a free/slave state, interpretations of the judges, and the support of African American networks.

- Write a thesis that responds to the focus question, “Were African Americans successful in using the judicial system to gain their freedom?”

Modifications:

- For the reading, the excerpts from Wherever There’s a Fight may be modified to the reading level of your students or read aloud to students.

- For the assessment, suggest possible thesis statements and have students discuss which thesis statement best responds to the focus question given the court case analysis.

Assessment:

Write a thesis statement that responds to the focus question, “How successful were African Americans who used the U.S. judicial system as a way to gain freedom prior to the Civil War?”

Reflection:

At the bottom of the Reading Organizer , have students reflect on the topic of African Americans fighting for freedom by completing the sentence frame, “I used to think…but now I know…”

Extension Ideas:

Possibilities to extend the learning from this lesson are

- Students can write an essay that compares and contrasts the cases of Bridget Mason, Archy Lee, and Archy Lee.

- Students can step into the shoes of one of the plaintiffs and write a letter of advice for other African Americans seeking freedom through the courts.

Lesson Downloads:

Next Lesson

Equal Protection: Yick Wo

8th Grade U.S. History

Overview & Background:

Chinese immigration to the United States began in the early 1800s as a result of civil unrest and poverty in China, and increased with the discovery of gold in California in 1849. As the population and economy of California grew, so did the population of Chinese immigrants. By 1880, the Chinese immigrant population of 75,000 made up almost 10% of the total state population.1 But as early as 1850, one year after the Gold Rush began, the state legislature passed laws targeting non-white foreigners and their ability to make a livelihood comparable to their white counterparts.2 When economic depression set in and fears of economic competition increased, Chinese immigrants were targeted as scapegoats.

A range of primary sources and media conveyed anti-Chinese sentiment: newspaper reports of lynchings and massacres, political cartoons exploiting racial stereotypes, taxation (beginning with the Foreign Miner’s Tax) and other legislation curbing rights provided in the Bill of Rights, and the virulent rhetoric of organized labor unions such as the Workingmen’s Party, all of which are shared in detail in Wherever There’s a Fight.

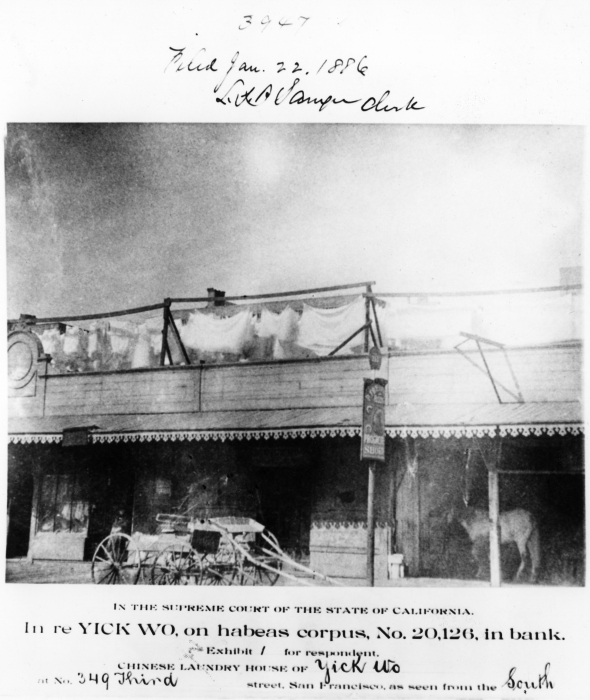

This lesson is a case study of Lee Yick, a Chinese immigrant laundry owner in San Francisco, who continued to operate his business in a wooden building without city approval to protest a San Francisco ordinance criminalizing the operation of laundries in wooden buildings without permission from the Board of Supervisors. After the sheriff arrested Lee Yick, his attorneys brought a lawsuit that reached the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that the San Francisco ordinance violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment because it was discriminatorily enforced against Chinese immigrants.

In an activity that explores the historical sources, students will apply their understanding of the Constitution and the Reconstruction Amendments to a situation in which a person was unfairly discriminated against. By closely reading the sources, students will be able to analyze the case, draw conclusions about the constitutional process, and make connections to 20th and 21st century cases of discrimination.

Focus Question & Teaching Thesis:

Focus Question:

As anti-Chinese feelings grew in the late 1800s, how did city and federal laws and enforcement of those laws support or deny Chinese laborers’rights to “equal protection under the law”?

Teaching Thesis:

Students will understand that city and federal laws did not uniformly support or deny Chinese laborers’rights to equal protection under the law. By examining one case study, students will see that enforcement of San Francisco’s wooden laundry ordinance denied equal protection to Chinese laundry owners. Students will also see that when the case was brought to the U.S. Supreme Court, the justices unanimously ruled that the city ordinance was unconstitutional because it violated the 14th Amendment, which forbids states from denying any person equal protection under the law. Moreover, the U.S. Supreme Court supported rights not only for Lee Yick, but also established the precedent that discriminatory enforcement of an otherwise neutral law is a violation of the equal protection clause of the 14th amendment. In addition, students will learn that although a law may seem impartial in its language, the use and analysis of context clues can help them to analyze laws for implied racial profiling. This lesson can be implemented in units on Immigration or Reconstruction.

History-Social Studies Standards:

8.3: Students understand the foundation of the American political system and the ways in which citizens participate in it.

8.12: Students analyze the transformation of the American economy and the changing social and political conditions in the United States in response to the Industrial Revolution.

- Examine the location and effects of urbanization, renewed immigration, and industrialization (e.g., the effects on social fabric of cities, wealth and economic opportunity, the conservation movement).

Learning Objectives:

- Students will be able to do a careful reading of historical sources and use context clues to interpret and analyze a case study

- Students will be able to understand the concept of equal protection under the law and its significance through a case study of the wooden laundry ordinance in San Francisco

Duration:

Two 45-minute periods

Materials:

Prior Knowledge/Context:

- Understanding of federalism, especially city-specific terms such as ordinances, city councils, and police and how they relate to state and federal laws

- Basic knowledge of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments (also known as the Reconstruction Amendments)

- Basic knowledge of the Gold Rush in California and the effects it had on immigration

Sequence of Activities:

- Have students fold a piece of paper to create four squares, then label each square “Strongly Agree”, “Agree”, “Disagree”, and “Strongly Disagree.”

- On the board, write the statement, “All laws are enforced equally no matter what.” Students should mark the square that represents their opinion on this statement, and think of 2-3 reasons to support their opinion.

- When students are ready, have them go to the four different corners in the room that are labeled “Strongly Agree”, “Agree”, “Disagree”, and “Strongly Disagree” that match their opinion. Within each corner group, students should form pairs or trios to share the reasons for their opinion. Have a few members of each corner group share out some of the reasons discussed, and record on the board in a 4-square under the statement. Allow students to ask clarifying questions, change their minds, and challenge reasons before returning to their seats to transition.

- Tell students that today’s lesson will examine this statement in the context of California in the 1880s. Have students share in small groups or as a whole class what they know of California during this time period. After students share, be sure to point out a few key time markers that you want them to keep in mind: (a) It is after the Gold Rush in 1849, (b) California has been a state in the union for about 30 years, (c) it is after the Civil War and Reconstruction, (d) and, it is after the passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments.

- Write the 14th Amendment on the board: “No State shall…deny to any person within its jurisdictionthe equal protection of the laws.” Ask students to think about its meaning and put it in their own words. Havestudents verbally share.

- As you pass out the Graphic Organizer and packet of historical sources to each student, tell students that they are going to look at a San Francisco case to investigate and judge for ourselves if there was equal protection under the law. We will begin with the actual law.

- Review the materials with the students: the Graphic Organizer is for students to write down a brief summary, interpretation, opinion, and questions for each source. Each historical source reveals a different piece of the entire case study, so that is why there is a column in the Graphic Organizer for students to state if they think this source shows evidence of equal protection under the law. Note that this reading and analysis part of the lesson may also be done cooperatively in pairs or groups.

- Using Sources A and B, model how you would like students to read and analyze the sources, before having students do so on their own or cooperatively with Sources C-F. Additional reading support may be needed here for vocabulary terms and syntax of legal language. Sources A and F contain complex legal language, and using translations of these primary sources can help facilitate students’understanding and interpretation of this ordinance and ruling.

- Regroup as an entire class, and discuss the case with the given evidence.

- Is the law fair and constitutional? Why or why not?

- How did each source change your opinion on the law?

- If you were in Lee Yick’s shoes, what would you do?

- Are there additional questions you have or evidence you need to make a decision whether or not this law is fair and constitutional?

- Before analyzing the last source, have students predict the ruling in this case.

- As a whole group, read and analyze the last source on the Supreme Court decision in Yick Wo v. Hopkins and respond to the two reading questions. Focus on what the ruling actually means, and have students share their interpretations in pairs to check for understanding.

- Open up class discussion about the significance of equal protection under the law in this case ruling. Draw four concentric circles and write the ruling in the center. Use these circles to record student discussion around the following questions:

- What did the ruling in Yick Wo v. Hopkins actually mean for Lee Yick?

- Expand the questions to consider what this ruling meant for Chinese laundry owners in San Francisco?

- What did this ruling mean for police and the San Francisco Board of Supervisors?

- Lastly, ask them to think about what this ruling means for us in the present in terms of law-making, law enforcement, and equal protection under the law?

- To reflect upon the lesson, return to the Four Corners activity that began the lesson. Have students reflect on the original statement, “All laws are enforced equally no matter what,” by completing the following sentence frame on their four-square sheet, “Before I learned about the Yick Wo case, I thought that (fill in with their original opinion and reasons). But after learning about the case, I now think that…”

Assessment:

- Successful completion of the graphic organizer demonstrates students’close reading and understanding of the historical sources.

- Participation in discussion and inclusion of equal protection under the law in the Four Corners reflection demonstrates students’understanding of the concept.

Modifications:

- The sources may need to be edited or translated, as was done for Source A, in order to be accessible for all reading levels. Students can be encouraged to attempt reading the original sources, and use the edited and translated versions to support their understanding of the originals.

- Visual images of the actual ordinance and Supreme Court rulings can be shown as artifacts with the historical sources.

- For Sources C and D, tables and graphs may be used to visually demonstrate the number of Chinese laundry owners who were discriminated against.

Extension Ideas:

- Create a timeline of significant court cases that relied on the equal protection clause.

- Compare and contrast other San Francisco ordinances to determine if they were enforced fairly towards Chinese immigrants.

- Apply students’understanding of equal protection under the law to a current ordinance or widely publicized cases of racial profiling or driving while black or brown (as described in Wherever There’s A Fight, p. 413-416).

- Debate the issue of equal protection for all persons in the context of current immigration issues.

Additional Resources:

Lesson Downloads:

[1] http://usinfo.org/docs/democracy/64.htm . Melvin Urofsky. Virginia Commonwealth University. July 29, 2010.

[2] See Foreign Miner’s Tax, Ch.1, p.23 (WTAF)

Next Lesson

Affirmative Action

11th and 12th Grade High School

Overview:

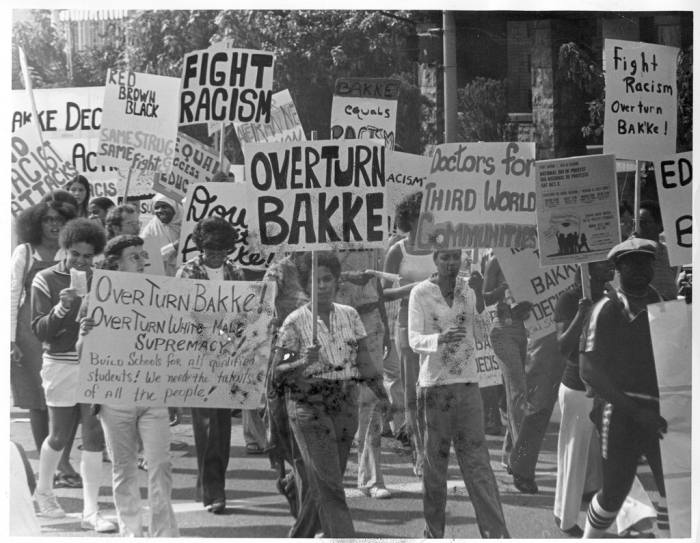

This lesson provides a focused look at affirmative action through a close examination of the 1978 Supreme Court case, Regents of the University of California v. Bakke and the 1996 California ballot initiative Proposition 209. Students will examine the goal of diversity as a “compelling state interest” and the claim of past discrimination to evaluate affirmative action strategies as a tool in the continued struggle for civil rights. This lesson accompanies an excerpt from Chapter 4, “The Fight for Racial Equality," in Wherever There’s a Fight. The text profiles the Bakke case and Proposition 209 to examine how shifting interpretations of the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause impact affirmative action strategies. This lesson could be paired with “The Fight for Racial Equality in Education” or the “Ballot Propositions and Civil Rights” lessons on the Wherever There’s a Fight website.

This lesson meets the state of California History-Social Science Content Standards for:

- 11th Grade U.S. History and Geography: 11.10 and 11.11 (Students analyze key court cases and developments in the evolution of civil rights including the Bakke case and California’s Proposition 209 along with discussion of racial equality as an ongoing social issue).

- 12th Grade Principles of American Democracy and Economics: 12.5 (Students examine the changing interpretations of the Bill of Rights with an emphasis on the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause and social controversies over these changing interpretations).

Learning Objectives:

Students will understand:

- Concepts underlying affirmative action as a civil rights strategy (a remedy to past discrimination, diversity as representative of equal opportunity)

- Different aspects of affirmative action strategies (quotas, race and class as factors in larger systemic policies aimed at achieving diversity and equality of opportunity)

- How a federal court decision has more far reaching consequences than a state court decision

- Shifting interpretations of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment

- The social context surrounding affirmative action controversies

Duration:

3-5 Class Periods; (*Classwork given here could be given for homework, group work given here could be done individually etc.)

Resources:

Text, Handout #1 , Handout #2 , and Handout #3

Warm Up:

Activities/Discussion: Using the quotes from Handout #1.

Pass out Handout #1 to students. Ask a student to read Quote #1 (below) from Handout #1 . Go over it again slowly to make sure students understand the definition. Solicit students to collectively fill in a “What I know” “What I think I know” and “What I want to know” chart for Affirmative Action (Each heading is over a separate column) on the board. Students should preface their comments to identify under which column heading they belong. Discuss each column, changing comments from one column to another as necessary.

QUOTE #1:

Affirmative Action is the policy of consciously setting racial, ethnic, religious, or other kinds of diversity as a goal within an organization. In order to meet this goal, an organization may purposely select people from certain groups that are underrepresented, or have historically been oppressed or denied equal opportunities. In that application of affirmative action, individuals of one or more of these minority backgrounds are preferred over those who do not have such characteristics; such a preferential scheme is sometimes effected through quotas, though this need not necessarily be so. (from Wikipedia)

After completing the WWW chart and accompanying discussion of Quote #1, read Quote #2 from Handout #1 (below). What is President Johnson saying about why anti-discrimination laws are not sufficient to ensure racial equality? Is affirmative action an appropriate strategy to “achieve equality as a fact and as a result”? Why or why not?

QUOTE #2:

“You do not take a man who for years has been hobbled by chains, liberate him, bring him to the starting line of a race, saying ‘you are free to compete with all the others,’ and still justly believe you have been completely fair…We seek not just freedom but opportunity…not just equality as a right and a theory, but equality as a fact and as a result.”

—President Lyndon Johnson, from a speech at Howard University (cited in Wherever There’s a Fight)

Quote #3 is from Barack Obama’s memoir, Dreams From My Father. Ask a student to read it aloud. What kind of “affirmative action” did Obama say that he benefited from? What do you think his point is in telling this story? What would he like people to think about?

QUOTE #3:

“…Started by missionaries in 1841, Punahou Academy had grown into a prestigious prep school, an incubator for island elites…It hadn’t been easy to get me in, my grandparents told her (my mother); there was a long waiting list, and I was considered only because of the intervention of Gramps’boss, who was an alumnus (my first experience with affirmative action, it seems, had little to do with race).

—Barack Obama, Dreams From My Father

Main Activity

There are two text excerpts:

- University of California v. Bakke: 1978 (pp. 157-160)

- Proposition 209: 1996 (pp. 160-163)

Reading/Writing:

Pass out Handout #2 to all students. (*Students can work in groups OR all students can read both sections.)

Read your section of the text quietly to your self or aloud together with your group. Answer the corresponding questions from Handout #2 . If you are reading silently record your responses in your notebook. When your group is all finished share your responses with one another—filling out your own notes if your group members included important details that you left out. If you are reading aloud together, each of you should write down your group’s responses to the following questions (the group members’responses could vary depending on the question—they don’t have to all be identical!):

Summarizing/Presenting:

When students have completed Handout #2 , ask each group to fill out the Summary Activity (Handout #3 ) collectively and choose 2 representatives from their group who will present this information to the class. During each presentation solicit questions/comments from the class. After each presentation have students write a “take home” message for each group (what they will remember about the Bakke case/Proposition 209 two weeks from now). When the presentations are done solicit a number of take home messages from each group presentation to be read aloud.

Whole group debrief:

- Is a diverse student population a legitimate goal for schools and universities? Government contracts? Why or why not? Why does the Supreme Court say that diversity is a “compelling state interest”?

- What other criteria, aside from race, could you consider to support a goal for a “diverse” student body?

- What claim is made for under-represented groups that underlies the need for “affirmative action”? (Why is it necessary?)

- Do you think that affirmative action is a good strategy for achieving diversity? Why or why not?

- Are ballot propositions an appropriate means to decide controversial issues like affirmative action? Why or why not?

- What tension do we see between the role of the court and the “will of the majority” with respect to Proposition 209?

Assessment Ideas:

Quiz, collect notes, create an “affirmative action” plan—what is your goal? How will you achieve it? Be sure to justify why your plan would pass muster according to the Bakke decision (affirmed in Grutter v. Bollinger in 2003 which upheld the affirmative action admissions policies of the University of Michigan Law School).

Lesson Downloads:

Next Lesson

Ballot Propositions and Civil Rights

11th and 12th Grade High School

Overview:

This lesson examines the history of ballot propositions in the struggle for equal rights in California. It accompanies excerpted text from Wherever There’s a Fight. The text excerpts profile key ballot initiatives from the 20th Century that played a role in supporting or battling against struggles for racial justice in California. Students examine the tension between “the voice of the majority” and the defense of minority rights and the role played by the judiciary in protecting the Constitutional rights of minority communities from injustices imposed by majority rule through the ballot initiative process. Each case study explores the social context that sometimes makes difficult the effort to protect and defend the rights of minority communities and populations in California.

This lesson meets the state of California History-Social Science Content Standards for:

- 11th Grade U.S. History and Geography; 11.11 (Students analyze major social problems and domestic policy issues in contemporary American society).

- 12th Grade Principles of American Democracy and Economics; 12.6. 12.7, 12.10 (Students examine features of direct democracy, e.g. ballot propositions, explain how conflicts between levels of government and branches of government are resolved, the relationship among federal, state and local jurisdictions in the Courts and the tension between majority rule and individual rights).

Learning Objectives:

Students will understand:

- The tension between majority rule as expressed through ballot initiatives and the role of the Courts to protect the Constitutional rights of minority populations

- How social context, fear and prejudice influence the ballot initiative process

- The difference between the legislative process and ballot initiatives as processes for making law in California

Duration:

Two class periods

Resources:

Text, and Handout #1

Activities:

Warm Up:

Students will do a “values barometer” for the following questions. Post a sign on one wall, “ALWAYS AGREE” and a sign on the opposite wall, “NEVER AGREE.” The teacher or a student reads each statement aloud and students QUIETLY stand and space themselves along a line in the classroom that reflects where they place themselves along the continuum between “always agree” with the statement and “never agree” with the statement. The teacher solicits student comments from different points along the continuum. As students comment, it is OK for classmates to adjust their own position along the continuum if what they heard changes where they want to stand. This activity invites rich discussion and works well if students can maintain quiet to hear and respond respectfully to classmates’ opinions.

Statement #1:

“Majority rule is always a good way to make decisions in a democracy.”

Statement #2:

“Voting is the most effective way to decide difficult controversial issues (e.g affirmative action, legal rights of undocumented immigrants, gay marriage).”

Tell students that this lesson will focus on the following ballot propositions in California and the role more generally of ballot propositions in the ongoing struggle for civil rights and equality for minority and vulnerable populations in California.

Main Activity

Students will work in groups to read the stories of a diverse group of Californians impacted by ballot initiatives in the 20th century. Each group will read an excerpt from Wherever There’s a Fight and answer a set of questions from Handout #1

Rights of the Criminally Accused

Pages 396-399

- Proposition 8; 1982, “Victims Bill of Rights”

- Proposition 184; 1994, “3 Strikes”

Gay Marriage

Pages 340-343

- Proposition 8; 2008 Same-Sex Marriage

School Busing

Pages 152-155

- Proposition 1: 1979 School Desegregation

- Proposition 21: 1972 “Student School Assignment Initiative”

Undocumented Immigrants

Pages 73-77

- Proposition 187: 1994 Undocumented Reporting

Fair Land/Housing Laws

Pages 53-55, 145-149

- Alien Land Law Initiative: 1920 Restrictions on Japanese American Property Ownership

- Proposition 14: 1964 Fair Housing Laws

People with HIV

Pages 331-333

- Proposition 64: 1986 Reporting/Quarantine

- Proposition 96: 1988 HIV Testing for Criminally Accused

- Proposition 102: 1988 Reporting/Sex Partners

For each group:

Read your section of the text quietly to yourself or aloud together (*the teacher can work this out if necessary). If you are reading silently record your responses to the questions in Handout #1 in your notebook. When your group is finished share your responses with one another—filling out your own notes if your group members included important details that you left out. If you are reading aloud together, each of you should write down your group’s responses to the questions (the group members’ responses could vary depending on the question—they don’t have to all be identical!):

After completing the Handout, have each group discuss their answers within the group. Choose one member of your group to participate on the Expert Panel to present to the class.

Expert Panel:

- Presenting Students: Sit or stand in front of the class together. Take turns telling the story of your set of ballot initiatives.

- Listening students: Ask questions! Record in your notebook one comment for each panel expert—how was this set of ballot initiatives like or unlike the one your group studied?

Whole group debrief:

-

Ask students to make a list of 3-5 key generalizations about the set of ballot initiatives we studied in class. Make a list on the board.

-

Read the following two quotes aloud. Ask students to reflect if these quotes describe the set of circumstances surrounding their set of ballot initiatives.

“The issue is not whether one judge can thwart the will of the people; rather the issue is whether the challenged enactment complies with our Constitution and Bill of Rights. Without a doubt, federal courts have no duty more important than to protect the rights and liberties of all Americans by considering and ruling on such issues, no matter how contentious or controversial they may be. This duty is certainly undiminished where the law under consideration comes directly from the ballot box and without the benefit of the legislative process.”

—U.S. District Court Judge Thelton Henderson from his preliminary injunction barring enforcement of Proposition 209

“…If fundamental rights can be stripped from a minority on a mere show of hands, why bother having courts and constitutions?”

—Evan Wolfson, from a letter to the New York Times in response to the success of California’s Proposition 8 banning same sex marriage, November 25, 2008

- U.S. District Court Judge Thelton Henderson argued that the ballot proposition process makes laws “without the benefit of the legislative process.” What do you think he meant? What is a “benefit of the legislative process” compared with ballot initiatives?

Who wins and who loses from ballot initiatives that involve civil rights issues? What are possible solutions?

Follow-Up Activities/Questions:

- Research the history of ballot initiatives in California

- Compare ballot initiatives in California with other states—do many states have a ballot initiative process like California?

Assessment Ideas:

Quiz, collect notes, evaluate oral participation

Lesson Downloads:

Next Lesson

The Right to Religious Freedom

11th and 12th Grade High School

Overview

This lesson is meant to accompany or follow a larger discussion of the Bill of Rights. It accompanies Chapter 8, “Keeping the Faith; the Right to Religious Freedom,” in Wherever There’s a Fight and highlights First Amendment issues around religious freedom. The text highlights case studies from 20th century California of minority populations struggling for their right to practice their faith—or the right not to practice any faith. These compelling stories make real and vivid the struggle to protect our First Amendment rights.

This lesson meets the state of California History-Social Science Content Standards for:

- 11th Grade U.S. History and Geography: 11.3 (principles of religious liberty through a study of the First Amendment)

- 12th Grade Principles of American Democracy and Economics: 12.2 and 12.5 (a close study of the Bill of Rights with an emphasis on judicial interpretation and public controversies)

Learning Objectives:

Students will understand:

- Why minority religious communities are vulnerable to violations of their religious liberty

- How times of social stress or war create a set of conditions that threaten civil liberties

- How the judicial branch can function to protect minority populations against popular prejudice as expressed through local officials

- How judges sometimes have to weigh Constitutional protections against competing claims, e.g. for public safety

- How the appeals process can function to maximize plaintiffs’opportunities to protect their rights and set a wider precedent to protect others in similar circumstances

Duration:

2-4 Class Periods; (*Classwork given here could be given for homework, group work given here could be done individually etc.)

Resources:

Text, markers, poster paper, tape/tacks, and Handout #1

Activities:

Warm Up:

Write the First Amendment on the board:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

Tell students that this lesson will focus on the first underlined part of the First Amendment: the Establishment and Free Exercise clauses of the First Amendment. Ask students to explain in their notebooks each of these clauses in their own words.

For discussion:

- For the establishment clause: Why is it important that our government not “make a law respecting an establishment of religion”? What would our country look like if we did have a state sanctioned religion? What issues would arise? For which populations? Can students name/describe countries that do not have an establishment clause?

- For the free exercise clause: What rights does this guarantee for us? Give examples of what “free exercise" rights might look like or why exercising these rights could become controversial.

- For both the Establishment clause and the Free Exercise clause, what value(s) do you think the framers of the Constitution wanted to protect? Why, or in what settings do you think these values could come under attack?

Main Activity

Tell students that they will work in groups to read the stories of a diverse group of Californians who had to go to court to protect their First Amendment rights from school, police, military, prison, state and federal officials during the 20th Century.

- Jehovah’s Witnesses (p.287-293)

- Navajo American Church (p.293-295)

- Black Muslims (p. 295-298)

- Logging Trucks through Sacred Land (p.298-301)

- From Playground to Graduation: Including All Students (p. 301-304)

- Institutionalized Religion (p. 304-305)

- Five Sacred Symbols (p.305-307)

(*You may want to combine some of the shorter sections into one group)

For each group:

Read your section of the text quietly to your self or aloud together. If you are reading silently record your responses to the following questions (see Handout #1) in your notebook. When you are all finished, share your responses with your group—filling out your own notes if your group members included important details that you left out. If you are reading aloud together, each group member should write down your group’s responses to the following questions (the group members’ responses could vary depending on the question—they don’t have to all be identical!):

- Who are the protagonists in this story (the main characters)? Give as much detail as is necessary for us to understand why they are important in this story.

- What happened (or was threatened to happen) to them?

- Give examples (if applicable) of how they suffered as a result of their rights being violated.

- Was there something about the context (the time period or the place where the events happened) that magnified or made stronger the effort to violate the protagonists’rights? Were there commonly held prejudices that impacted their experience?

- Choose language (a phrase or set of sentences) from a judge’s decision (or an attorney’s argument) that feels compelling to you and write it down—why did you choose this quote to highlight?

- What, in this story, was surprising to you? Why was it surprising?

- For the government officials who moved to violate someone’s First Amendment rights—how do you think they would describe or defend their actions? Why did they do it (or plan/want to do it?) What values/customs/ideas do you think they were acting to protect?

Choose a quote from your section that your group feels is a compelling statement about the issues raised in your section—write it on a large piece of poster paper and post it on the wall.

Fishbowl:

Each group chooses two representatives. Each set of representatives will be interviewed in turn by the teacher while the rest of the class sits in a circle around them. The interview will largely follow the questions. While students listen to each interview (not including their own group), they write down 3 things they hear that caught their attention and/or are essential to understanding this story OR replace one of those with a burning question they have about the case.

Each interview will conclude with a group member (not one of the two representatives) reading their groups’ quote that is posted on the wall and explaining why their group felt it was important to share. After each interview, the teacher will solicit both comments and questions from listening students that they had written down in their notes during the interview.

Whole group debrief:

- Did the people who fought for their rights consider themselves civil rights activists or regular people? What made them take a stand? Can you relate to them—why or why not?

- In what ways do people suffer when they take a stand to protect their First Amendment rights?

- For the school or government officials who acted to violate someone’s First Amendment protections—what pressures do you think they felt? How would they describe or defend their own actions? Can you relate to their arguments? Why or why not?

- Of the stories we studied, which of the people involved would you most like to meet and why? What would you tell them? Why does their story matter to you?

Assessment Ideas:

- Collect and review student notebooks

- Put together a quiz based on Fishbowl activity/text assignment

- Ask students to write an “exit card” using their notes to write a short paragraph highlighting what they will remember about the struggles for religious freedom

Lesson Downloads:

Next Lesson

The Fight for Racial Equality in Education

11th and 12th Grade High School

Overview:

This lesson broadens the study of the ongoing struggle for racial equality in the schools beyond Brown v. Board of Education through an examination of the judiciary’s role in safeguarding the rights of communities of color to a quality public education. It accompanies Chapter 4, “The Fight for Racial Equality,” in Wherever There’s a Fight. The text excerpts profile key 14th Amendment Equal Protection Clause cases that show the range of strategies used by individuals and communities in their struggle to access a quality public education. These compelling stories make vivid the struggle for racial equality in California public schools. This lesson assumes that students have some basic knowledge of the Bill of Rights.

This lesson meets the state of California History-Social Science Content Standards for:

- 11th Grade U.S. History and Geography: 11.10 and 11.11 (Students analyze key court cases and developments in the evolution of civil rights including the Bakke case and California’s Proposition 209 along with discussion of racial equality as an ongoing social issue).

- 12th Grade Principles of American Democracy and Economics: 12.5 (Students examine the changing interpretations of the Bill of Rights over time with an emphasis on the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause and social controversies attendant to changing interpretations over time).

Learning Objectives:

Students will understand:

- How the battle by different ethnic and racial communities to end school segregation in California in the late19th and first part of the 20th centuries predated more well known efforts by African Americans in Southern states decades later to fight for integrated public schools

- How the Mexican-American community in southern California through Mendez v. Westminster in the 1940s used groundbreaking legal strategies to challenge school segregation that were later used in Brown v. Board of Education

- How minority populations use a range of political strategies (e.g., protests, letter writing campaigns, ballot measures) in addition to judicial strategies to fight for equality in public education

- The difference between de facto and de jure segregation, the impact of residential segregation on school segregation and the unsuccessful struggle to get the courts to remedy de facto segregation

- The importance of class action suits as a strategy in the struggle for racial equality in education

Duration:

3-5 Class Periods; (*Classwork given here could be given for homework, group work given here could be done individually etc.)

Resources:

Text excerpts, copies of the photo “Oriental School,” Handout #1 and Handout #2 from Lesson packet

Activities:

Warm Up:

Post a number of copies of the photo, “Oriental School” (download here) around the classroom. Have students examine the photo closely. (Note: Prior to World War II, students saluted the flag, like the children in the photo, with a straight-arm salute. The practice was eliminated after the gesture’s association with Nazi Germany.)

Discussion:

- What details allow you to guess the time period of this photo?

- What do you notice about the students? How are they dressed and what does that tell you (are they immigrants? People from one ethnic/racial group? What are they doing? Why?)

- If the students in that photo could speak to you—what do you think they would tell you about why they are in school? Their hopes and dreams for the future? Do you think their hopes and dreams could be characterized as “American”? Why or why not?

Tell students that this lesson will focus on the part of the 14th Amendment excerpted and written on the board: the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment:

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

- Ask students to copy the text into their notebooks and underline any words they don’t understand. Go over this vocabulary together.

- Ask students to explain what the clause means in plain English

- How does the 14th Amendment strengthen citizens’ protection from government? (make sure students understand that the 14th Amendment extends protection against the actions of the federal government to now include actions from state governments as well)

For discussion:

- In Plessy v. Ferguson (briefly review if necessary), the Supreme Court established the legal concept of “separate but equal” to defend segregated rail cars. What do you think the students in the “Oriental School” photo would say about this concept? Do you think “separate but equal” is a useful tool for setting up public schools? Always? Sometimes? Never?

Main Activity

Students will work in groups to read the stories of a diverse group of Californians who had to go to court to fight for equal access to quality public schools in the 19th and 20th centuries. Each group will read an excerpt from Chapter 4, “Under Color of Law: The Fight for Racial Equality,” in Wherever There’s a Fight and answer questions based on the text (See Handout #1—note that each group has a different set of questions). *Review text sections beforehand and assign groups accordingly—some have more difficult text sections.

Groups:

- 19th Century California (p. 129-132)

- Mendez v. Westminster (p.133-137)

- School Busing in Los Angeles County (p. 152-155)

- Williams v. California (p. 155-157)

Reading/Writing:

-

Read your section of the text quietly to yourself or aloud together with your group. If you are reading silently record your responses to the questions on Handout #1 in your notebook. When you are all finished, share your responses with one another—filling out your own notes if your group members included important details that you left out. If you are reading aloud together, each of you should write down your group’s responses to the questions (the group members’responses could vary depending on the question—they don’t have to all be identical!)

-

When your group has finished answering the questions, complete Handout #2 for a summary activity. Using your responses to Handout #1 and small group discussion, take notes for an oral summary of your section that you will share in a partner activity with your classmates in other groups.

Partner Sharing:

-

Using your summary outline from Handout #2, choose a partner (or the teacher will make the matches) from one of the three other groups. Each partner has 3 minutes to make a presentation and

-

minutes to answer any questions. Change partners until each student has given and heard 3 presentations.

Whole Group Debrief:

- Getting the legislature to pass a law or initiating a ballot proposition are political strategies—why are they sometimes not successful tools for minority populations? Why is seeking a “judicial remedy” sometimes a more effective strategy?

- How are “class action suits” a powerful tool for making change? Give an example from your reading of a successful class action suit?

- What is the difference between de facto and de jure segregation? Do you agree with the U.S. Supreme Court decision in 1982 that said the courts could only order desegregation if it was proven that a school district intentionally segregated students? Why or why not?

- Ask students to look in their notebooks at the text they copied over of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment:

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Why is this clause so important to people fighting for racial equality in the schools?

- On a half-piece of paper write one thing you learned about the struggle for racial equality in California schools that you'll remember two weeks from now. The teacher can solicit students to share their responses.

Assessment Ideas:

Quiz, collect and assess Handout #1 and Handout #2 , assess quality of oral presentations

Lesson Downloads: